Black women have used, controlled, and shaped food spaces to their families’ and communities’ advantage for hundreds of years in the United States. From the first enslaved women brought to New Amsterdam in 1619 to women today, powerful Black women have used food as a lever for social transformation. Black women’s food-related agency has spanned from the kitchen table to policy circles, though this agency is often overlooked in research, policy, and popular discourse. This Juneteenth we reflect on the historic contributions and present-day work of Black women to advance food justice in East Buffalo and beyond.

Enslaved Black women labored in the domestic food space and in the fields. Slave owners restricted access to food as a method of control, giving Black families the unwanted scraps. Thus, Black communities, in particular Black women, had to adapt the foods allowed by white slave owners. To feed their families and communities, Black women turned to the indigenous traditions of North America, including what is now known as Southern Barbecue, traditions incorrectly attributed to white Southern identity. Despite the horrific conditions, enslaved Black people used food to build community, even when community building was a powerful and dangerous form of rebellion. Through food, Black people created sustenance not only for the body but also for the soul.

During the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, food became a marker of cultural heritage, something valued as a connection to African ancestry. Quickly, Southern Black people used soul food to create a southern identity, in a place of deep segregation. Soul food and, more importantly, home cooked food became central to Blackness and identity, especially as many Black people were forbidden from restaurants and diners. The reclamation of soul food during the Civil Rights Era was nurtured by the identity Black women created around the kitchen table. Many Black women built their selfhood at their mothers’ and grandmothers’ kitchen tables. Thus, the home kitchen becomes more than a space of survival and sustenance; it was and remains the central point of community. In addition to cooking their own food, Black women called on their ancestral traditions of farming to grow their own food. Food activist and leader, Fannie Lou Hamer and her Freedom Farm connected her experience as a Black woman to her agrarian knowledge and her belief in the economic potential of farming for Black communities. Through the home and the land, Black women organized around food to support their communities.

Drawing on the work of Black women within their communities, high profile Civil Rights organizations, such as the Black Panther Party (BPP) began to use food as a tool for revolution and resistance. Indeed, “feeding the revolution” comes from the tradition of Black women who fed their families and communities for survival.

Food is often pushed to the side when considering racial politics, but by understanding the necessity of survival through their history and lived experience, Black women have pushed food to the forefront. They are not agentless people, but rather bodies of resistance using organizing, farming, and entrepreneurship for survival. While not every individual movement is successful, community organizing displays the necessity of self-reliance and forges community networks. In fact, the resistance work ubiquitous in Black food justice movements today can find roots in past and present Black feminist thought and work. As the food justice movement grows, Black women assert their food voices and challenge the status quo, standing on the shoulders of their ancestors.

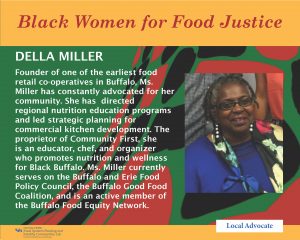

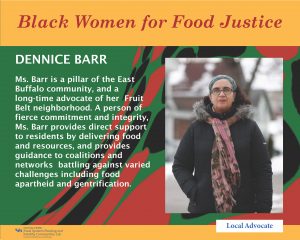

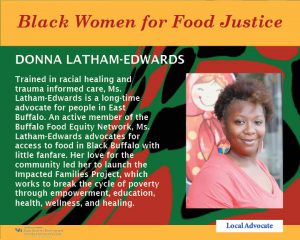

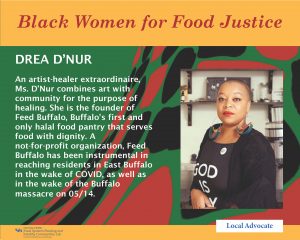

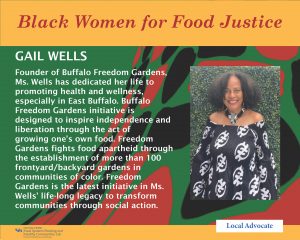

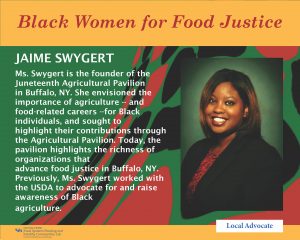

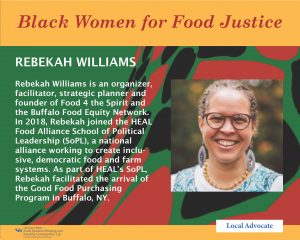

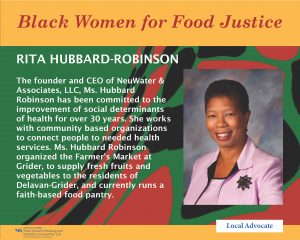

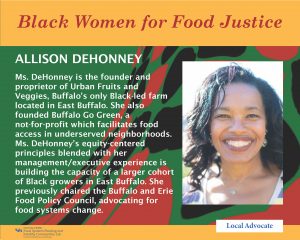

A display at Juneteenth Agricultural Pavilion in Buffalo honored Black women leaders who have inspired and enacted change in East Buffalo’s food system. The women featured in the pavilion included local leaders as well as national leaders. We share brief descriptions of local leaders with you digitally here. Local leaders were nominated by members of the Buffalo Food Equity Network and research was conducted by the Food Lab.

Credits for post:

Shireen Guru – Historical research

Lorna Georges – Design research